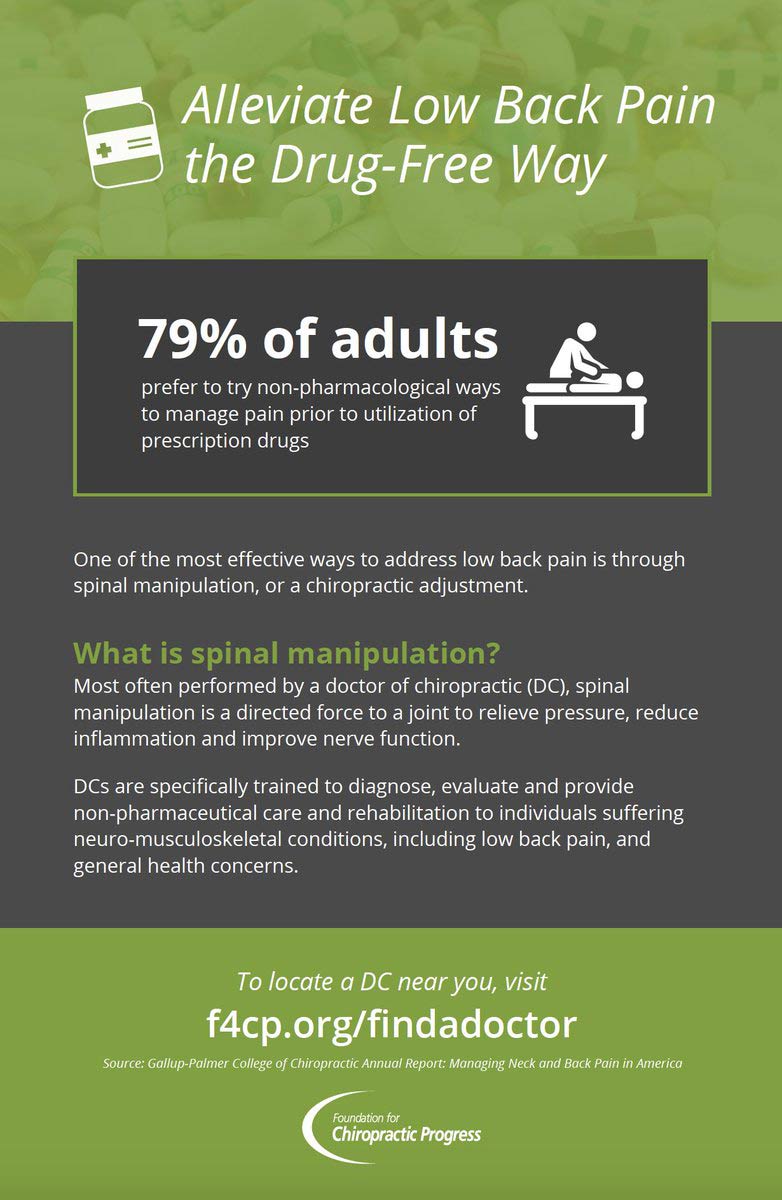

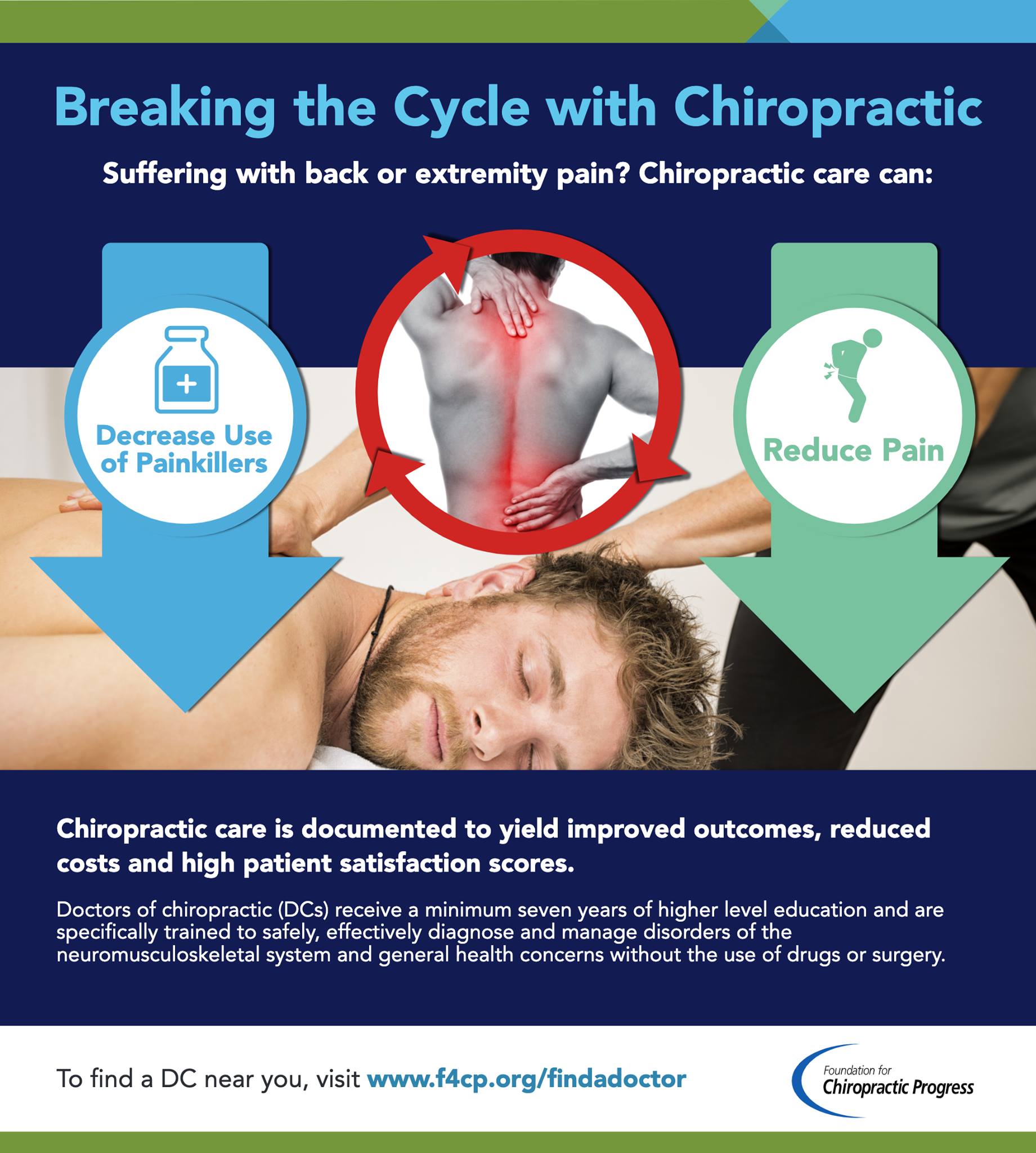

These medications carry the risk of depression, including suicidal symptoms, as a possible adverse effect. There are safer pain management approaches — see your doctor of chiropractic for drug-free pain relief.

More than a third of Americans are estimated to be taking at least one prescription medication that carries the risk of depression, including suicidal symptoms, as a possible adverse effect—and they may have no idea—according to a study published this week in JAMA.

The study is an observational one, meaning it can only identify associations and not whether common drugs are causing depression or suicide in people. Still, the researchers found some worrying links between the use of common medications and the potential for depression. Most notably, the researchers found that those taking three or more medications with depression risks had a greater chance of self-reporting depressive symptoms on a nine-question survey. Their rate of self-reported depressive symptoms was 15.3 percent, about double the rate reported by those taking just one drug with a risk of depression and about triple the rate of those taking no medications with risk of depression.

This is particularly concerning, the researchers suggest, because patients may not make a connection between their depressive symptoms and the drugs they’re taking. Drugs with risks of depression are very common, they may not have clear warning labels, and some can even be purchased as over-the-counter medications. The most common of them are drugs such as hormonal birth control, beta-blockers (used for conditions such as high blood pressure, heart attacks, and migraines), and proton-pump inhibitors (used for acid reflux).

In all, there are more than 200 medications in use in the US that list depression or suicidal symptoms as possible adverse effects. The only class of drugs with a “black-box warning”—the Food and Drug Administration’s clearest and gravest warning label—for suicidal risks are antidepressants.

While the study is just a starting point for probing the potential role of prescription drugs in depression and suicide, the authors argue that now is the time for more research. The study comes as public health researchers report high rates of depression and suicide in the country. Between 2013 and 2016, 8.1 percent of American adults had depression in a given two-week period. Last week, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention released nationwide figuresshowing that suicide rates had increased nearly 30 percent overall between 1999 and 2016, with nearly every state seeing increases. Of those who committed suicide, 54 percent were not known to have a mental health condition such as depression.

Dreary data

The authors of the JAMA study—led by Dima Mazen Qato, a pharmacist and health policy expert at the University of Illinois at Chicago—say that more research into the links between drugs and depressive symptoms are needed. In the meantime, they suggest that doctors should better communicate risks to patients who are taking medications with potential side effects of depression and suicide.

Their conclusions are based on data from a nationally representative observational survey that collected information between 2005 and 2014 on 26,192 participants aged 18 or over. Overall, 37.2 percent of participants reported taking at least one medication that listed depression as a potential adverse effect, with 7.5 percent of those taking three or more.

The prevalence of self-reported depressive symptoms rose from 6.9 percent in the participants taking just one risky drug to 9.5 percent in those taking two, and to 15.3 percent in those taking three or more. Those taking no drugs with a risk of depression had a rate of self-reported depressive symptoms of 4.7 percent. Thus, the more drugs with a risk of depression, the greater the likelihood of depressive symptoms, the researchers found.

This held up when the researchers excluded data on patients who were taking psychotropic drugs—ones that intended to alter a mental state. It also held when researchers compared rates of depressive symptoms just in patients with high blood pressure, comparing those that took three or more drugs with a depression risk and those who took drugs with no such risk.

The researchers also noted that the situation may be getting worse over time. Breaking the data out across the survey period, they found that use of drugs with a risk of depression increased from 35 percent in 2005-2006 data to 38.4 percent in the 2013-2014 data. Between those time frames, use of three or more risky drugs increased from 6.9 percent to 9.5 percent.

The study had plenty of limitations in addition to being an observational study. For one thing, the survey data didn’t include information on mental health history. So, it’s not possible to sort out the patients who had preexisting or independent cases of depression. Also, the self-reported survey on depressive symptoms is a screening tool, not a diagnostic. And self-reported data can yield skewed or incomplete pictures of mental health.

Still, the authors conclude that “polypharmacy” (taking more than one drug at the same time) is a concern for medications with risk of depression—and one that requires more research.